|

Jack London and

Fleeing Refugees Jack

London, San Francisco-born author of The

Call of the Wild, The Sea-Wolf,

and White Fang, was living on

his ranch in Sonoma Valley, north of San Francisco, at the time of the

1906 earthquake and fire. He and his wife, Charmian, arrived in the city

by ferryboat and then wandered the devastated streets for two days and

nights. He recounted his experiences in an article later published in Collier’s magazine.

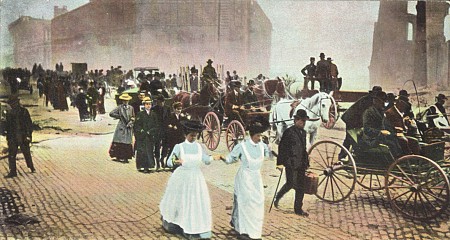

Refugees

fleeing along Market Street while the city burned. Remarkable as it may seem, Wednesday

night while the whole city crashed and roared into ruin, was a quiet

night. There were no crowds. There was no shouting and yelling. There

was no hysteria, no disorder. I passed Wednesday night in the path of

the advancing flames, and in all those terrible hours I saw not one

woman who wept, not one man who was excited, not one person who was in

the slightest degree panic stricken. Before the flames, throughout the

night, fled tens of thousands of homeless ones. Some were wrapped in

blankets. Others carried bundles of bedding and dear household

treasures. Sometimes a whole family was harnessed to a carriage or

delivery wagon that was weighted down with their possessions. Baby

buggies, toy wagons, and go-carts were used as trucks, while every other

person was dragging a trunk. Yet everybody was gracious. The most

perfect courtesy obtained. Never in all San Francisco's history, were

her people so kind and courteous as on this night of terror. All night these tens of thousands fled

before the flames. Many of them, the poor people from the labor ghetto,

had fled all day as well. They had left their homes burdened with

possessions. Now and again they lightened up, flinging out upon the

street clothing and treasures they had dragged for miles. They held on longest to their trunks,

and over these trunks many a strong man broke his heart that night. The

hills of San Francisco are steep, and up these hills, mile after mile,

were the trunks dragged. Everywhere were trunks, with across them lying

their exhausted owners, men and women. Before the march of the flames

were flung picket lines of soldiers. And a block at a time, as the

flames advanced, these pickets retreated. One of their tasks was to keep

the trunk-pullers moving. The exhausted creatures, stirred on by the

menace of bayonets, would arise and struggle up the steep pavements,

pausing from weakness every five or ten feet. Often, after surmounting a

heart-breaking hill, they would find another wall of flame advancing

upon them at right angles and be compelled to change anew the line of

their retreat. In the end, completely played out, after toiling for a

dozen hours like giants, thousands of them were compelled to abandon

their trunks. Here the shopkeepers and soft members of the middle class

were at a disadvantage. But the working-men dug holes in vacant lots and

backyards and buried their trunks. The

above is an extract of an account in Malcolm E. Barker’s book, Three Fearful Days: San Francisco Memoirs of the 1906 earthquake &

fire (Londonborn Publications, San Francisco, 1998).

|